Summarizes the main developments that have characterized the last decade of fashion in the twentieth century, and outlines key issues that have arisen from major changes taking place during the course of the twentieth century. In turn, these issues pose implicit questions that only future events can answer. Each issue has been addressed in a mutually exclusive format. This does not deny that an interrelationship or overlap exists but, rather, attempts to highlight topics that are worthy of individual consideration by today’s fashion reader.

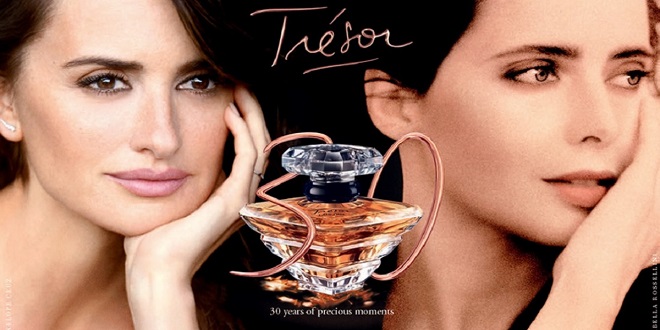

The death of haute couture?

By the mid-1990s, it seemed that French haute couture was no longer sustainable. What had happened to Western designers by the early 1990s London journalist Juliet Herd (1991) wrote of the unbridled indulgence that sounded ‘the death knell of haute couture at the start of the 1990s. This ‘extinction of the Paris couture industry was reaffixed rimed by Pierre Berge, the high-profile head of Yves Saint Laurent when he stated that ‘Haute couture will be dead in ten years’ time’ (Herd, 1991).

The French prime minister, who believed the French fashion industry ‘needed an overhaul’ in order to survive, called a summit meeting to discuss the troubles of the ailing $3.3 billion export industry. It seems that the exclusivity of the Chambers Syndicate, the industry’s powerful authority, prevented the inclusion of the younger, more avant-garde designers in the ‘club’, and that wealthy young clients were turning to prêt-à-porter as haute couture ‘seemed to be running out of ideas.

Herd argues that ‘the lack of originality among top designers was highlighted at the French collections’, where one fashion expert observed that ‘many top couturiers appeared to be wandering up blind alleys, uncertain of their role’. Signify cantle, there were twenty-one haute couture houses in Paris at this time, according to the Chambers Syndical, which regarded haute couture (and not prêt-à-porter) as the backbone of their business.

Similarly, the 7 November 1991 issue of L’Expressasked a pointed question: ‘Who broke the desired machine?’ Historian Chinbone (1993) argues that: ‘Many people have begun to feel that the current fi n de siècle is marked by an unhealthy atmosphere. The problems of Aids, unemployment and economic recession are complicated by the political upheaval and ethnic nationalism resulting from the recent collapse of companies and the Soviet empire’ (1993: 316).

Placing this phenomenon within a social and historical context, could it be that Western fashion had exhausted its endless appetite for change by the 1990s? In their constant search for novelty, some designers looked back to previous historical periods, while others found a need to react to or contradict that which had gone immediacylately before. This lack of direction seemed to be broadcast in the growing superfine calamity of styles that led Suzy Meknes, Fashion Editor of the International Herald Tribune, to comment on the bankruptcy of innovation and new ideas (Meknes, 2000).

Last word

Yves Saint Laurent’s haute couture was losing $20 million a year when it closed its doors in 2002. There were only eleven elite haute couture malisons’ remaining in Paris, as few clients were willing to pay in excess of $90,000 for a made-to-measure garment. Saint Laurent had 120 remaining regular customers, including France’s fi rut lady, Bernadette Chirac. Bergen, the company chairman, finally admitted: ‘Let’s not kid ourselves—haute couture is finished and it’s better to get out before it disappears completely’ (quoted in The Australian, 2 November 2002).